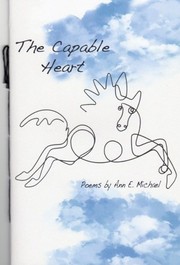

The Capable HeartWorldCat•LibraryThing•Google Books•BookFinder

The Capable HeartWorldCat•LibraryThing•Google Books•BookFinder

This quietly powerful collection made me care about horses — and not merely because the title derives from a translation of a passage in my favorite work of philosophy, Zhuangzi. Though I have some friends who are into horses, the horse-riding culture has always been pretty alien to me, and on rare close encounters with the beasts I’ve felt a bit intimidated, to be honest. But the narrator, too, was a stranger to horses, as she explains in “Ways We Are Alike”:

I wanted a way to embrace

my daughter’s fascination.to overcome my own fear, with carrots,

with a lead rope and soft brush.I touched the withers and the

warm, broad chest;I held the lead. Let pulsing lips

explore my hands, my jacket.

Horse and author go on to explore each other, in this poem and as the cycle progresses. Michael ponders the attraction that girls and women have toward horses:

Women who have re-centered their lives owing, in part, to horses,

are shy of nothing, strong as horses…

(“Horsewomen”)

She also examines the interplay between domestication or domesticity and rebellion, as in “Domestic Mutinies”:

Sometimes my outrage gallops

hard inside my ribs

and I feel like Chuang Tzu’s

outlaw horses: domesticated, enslaved,

& utterly capable, in their hearts.

“Dancing Horses” come into their own in a snowstorm:

Now

manes are streaming, necks arched,

an unrestrained blizzard

in the corral where they

toss off the long-bred bit

that is obedience.Sublimating domesticity,

the screaming stallion wind:

their unbroken past.

In “Boss Mare,” a woman named Rosie embodies the strong individualism of a lead horse.

I can just see her cribbing

her stall, bossing the other mares around: stay back,

do things my way.Not that the other horses mind. She wields the lead ropes,

she calls at the corral gate and most of them come running—

she’s boss mare.

Is it a sign of the author’s own rebellious streak that she never writes the most obvious poem: about riding a horse herself? The rider is always the daughter, and though sometimes the author or narrator takes the place of the horse, as in “Mare’s Nest” —

Notes and

photos, music, a belt

or rumpled jeans, slippers

slipped off, on, entropy

maybe. Lie in straw, back

toward the stall door. Sniff,

huff, wicker, snore.

— other times, as in “The Indoor Ring,” her gaze shifts away from horses, and she turns to watch swallows diving instead, or — in “Watching a Child Ride Horseback Through Snow” — gets distracted by a preening blue jay and loses sight of horse and rider. The domesticity-vs.-rebellion theme is developed strongly enough that a couple of poems, “Housekeeping” and “Anger Good As Hope,” avoid mentioning horses altogether. But even then, the reader feels the warm breath of the horse and hears it nicker.

This is, above all, a wise book — even if the author would probably disavow any personal store of wisdom, and attribute what lessons she’s gleaned to the horses themselves. As in Zhuangzi, they are teachers by dint of the purity of their natures and their connection to the earth over which they fly, but as such they are not to be taken too seriously. “Evolution of the Horse” ends on a pun; “Stray Horses” are capable of “astonishing vulgarity” and are “pitiable, oafish, indelible as my own failures”; and the “big quarterhorse” in the closing poem, “Riding-School Zendo,” mimes a Zen master with his horsehair whisk.

The stories we tell about horses can never encompass the full strangeness of their being, of course, as poems such as “Putting Down the Mare” and “The Difficult Birth” remind us. And this too is a source of wisdom for those who pay attention as well as Michael does:

We survive drought. Or we do not.

The paint goes back to her grazing,

unencumbered by memory. Perhaps,

next May, I will tell a different story.

Perhaps not.